by Peter Elkind

This story was originally published by ProPublica

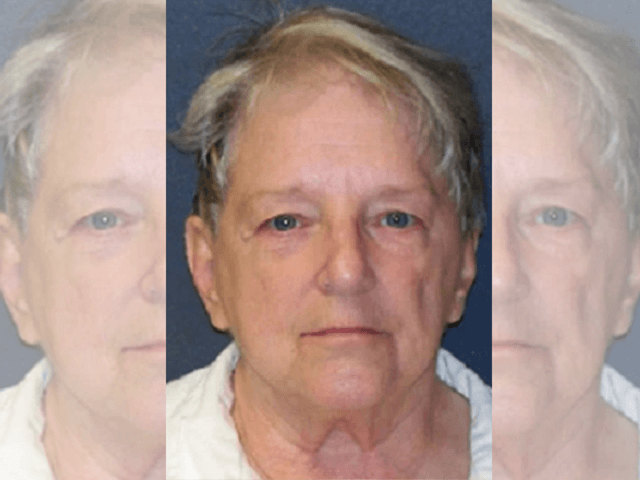

Former nurse Genene Jones, suspected for decades of killing more than a dozen children but tried and convicted for only one, pleaded guilty Thursday in San Antonio to the murder of an 11-month-old boy in 1981 and was sentenced to life in prison. Jones’ sudden reversal — she had previously pleaded not guilty to five murder charges filed in 2017 — confirms her place as a serial baby-killer and ends a twisted criminal-justice saga that has played out over four decades.

Jones, 69, unexpectedly sought the plea deal last week, just a month before she was to go to trial in the first of the five murder charges: for the death of Joshua Sawyer on Dec. 12, 1981.

Jones’ crimes reemerged into prominence in recent years after victims’ relatives learned that she was scheduled for mandatory release in March 2018. A San Antonio prosecutor reinvestigated some of the crimes and brought the five indictments in 2017.

The events they cover date back to Jones’ work in the pediatric intensive-care unit at San Antonio’s charity hospital (now called University Hospital) during the years Ronald Reagan occupied the White House. The five victims ranged in age from 3 months to 2 years. Jones’ alleged murder weapons: an array of powerful drugs.

Jones is not expected to be eligible to even apply for possible parole until around 2038. That fulfills the goal of her victims’ aging parents (three have already died), who for years pressed San Antonio prosecutors to bring new murder cases to block Jones’ release.

Dressed in blue scrubs and wearing dark glasses, with short white hair, Jones arrived in the courtroom using a walker. After signing and confirming her guilty plea, she watched, but remained silent and expressionless, as the presiding judge, and then tearful family members, assailed her for her crimes.

State Judge Frank Castro declared that Jones’ life sentence “doesn’t come close to what you did to these families and the tragedy that you caused. You took God’s little precious gift: babies, defenseless, innocent … I truly believe your ultimate judgment is in the next life.”

Connie Weeks, Joshua Sawyer’s mother, told Jones, “I’m glad that you will never see daylight.” Weeks spoke those words while standing just feet away from her child’s killer, delivering her victim impact statement in court, along with four other family members. “I hope you live a long and miserable life behind bars.”

The goal of successfully prosecuting the San Antonio cases long seemed unattainable.

When Jones worked at Bexar County Hospital during the early 1980s, unexpected emergencies and deaths became so frequent that her 3 to 11 p.m. work hours became known among medical staff as “the Death Shift.” But the ICU treated desperately ill children, and ironclad proof she was responsible proved elusive. Instead of alerting criminal authorities to investigate, the hospital — after several secret internal probes — ousted Jones (but gave her a good recommendation) under the cover of upgrading the ICU to an all-RN staff.

Jones then moved on to a small-town pediatric clinic in nearby Kerrville, where, in a single month, eight children with routine medical problems stopped breathing; one of them died. After evidence surfaced that Jones had injected the children in Kerrville with a paralyzing muscle relaxant, Jones was convicted of murdering 15-month-old Chelsea McClellan and received a 99-year prison sentence.

A lengthy criminal investigation in San Antonio included a Centers for Disease Control study that showed patients during a 15-month “epidemic period” were 10 times more likely to die on a shift that Jones worked. Yet the district attorney declined to bring murder charges, reasoning that proof in any single case was too elusive and Jones would never walk free anyway. (A conviction for injuring a child who survived resulted in a concurrent 60-year sentence.)

It was decades later that relatives of Jones’ victims realized a Texas law designed to ease prison overcrowding could result in her walking free. Awarding credit for “good time,” it mandated Jones’ release in early 2018, after she had served about a third of her sentence.

Alarmed, Petti McClellan, Chelsea’s mother, working with Houston victims advocate Andy Kahan, led a campaign to press prosecutors to take the only step possible to keep Jones locked up: bringing new murder charges from among the decades-earlier hospital deaths.

That effort went nowhere until the election of a new Bexar County district attorney, Nico LaHood, in November 2014. An aggressive young assistant DA named Jason Goss, who was just 1 year old when Jones committed her crimes, began digging through dusty boxes of courthouse files from the 1980s Jones investigation. Goss and LaHood brought the first of the new murder charges in March 2017, accusing Jones of killing Joshua Sawyer with a massive overdose of the anti-seizure drug Dilantin.

Four more indictments followed, each accompanied by a $1 million bond that assured Jones remained in the Bexar County jail pending trial even after her mandatory release date.

For the families, who had waited decades to attain any measure of justice in the deaths of their loved ones, the case remained an emotional roller coaster.

LaHood’s 2018 defeat in a bitter primary race against his onetime law partner, Joe Gonzales, assured that lead prosecutor Goss would depart, sparking fears the Jones case would be neglected or even abandoned. That concern proved unfounded; Gonzales assigned Catherine Babbitt, his veteran major crimes chief, to lead the trial team. Jones’ lawyers brought motions to throw out the indictments. The judge rejected them.

Through it all, Petti McClellan, by then a retired nurse, provided support to the San Antonio moms: testifying before the grand juries and attending every court hearing and meeting with prosecutors. In June 2019, at age 64, she suddenly died. Six months later, Juanita Villarreal, the mother of one of the five San Antonio babies Jones was charged with murdering — Paul, just 3 months old — also died.

At one point, Jones had appeared willing to plead guilty to lesser charges that would keep her behind bars, but not to murder. Prosecutors told ProPublica that Jones didn’t want to be known as a serial murderer. “In Genene’s mind, she would not be known as a serial killer,” Babbitt said.

But that was months ago, leaving the Sawyer case headed toward a high-profile courtroom showdown — until last week.

That’s when, just two days after receiving a submission listing 200 potential witnesses and 97 different acts the DA’s team might raise during her trial, Jones’ lawyers raised the prospect of a plea deal, according to the lead prosecutor, Babbitt. “I think she realized we meant business,” she said.

Thursday’s agreement provides for dismissal of the four other murder cases, but a condition of the deal was that each of the five families would be able to give a victim impact statement, directly addressing Jones.

The plea agreement will require Jones to serve 20 years before first becoming eligible for parole, with credit for her two years behind bars awaiting trial. That would likely take Jones to 2038, when she would be 87 years old.

“If the parole board wants to deny her every time she comes up and keep her until she takes her dying breath, that’s their prerogative and our preference,” Babbitt said. “Why on earth would she be allowed to walk among us?”

Jones had formally maintained her innocence until Thursday, pleading not guilty to the five murders, even after informally offering semi-confessional statements over the years on at least two occasions. In a 1998 prison interview, detailed at an April 2018 court hearing, a tearful Jones reportedly told a parole officer: “I really did kill those babies.”

And in a 2011 letter to the Texas Board of Nursing, reported by ProPublica in June 2017, Jones professed feeling guilt. Responding to formal proceedings to revoke her suspended nursing license before her potential release, she wrote from prison apologizing “for the damage I did to all because of my crime.” Added Jones: “I look back now on what I did and agree with you that it was heinous, that I was heinous.”

Thursday’s events unfolded in a nearly full courtroom, with players from key events in the decadeslong case — including Goss and LaHood — in attendance to see it brought to a conclusion.

After the formal proceedings were over, Jones stood up and quickly wheeled herself out a side door of the courtroom.

Peter Elkind, a senior reporter with ProPublica, first wrote about the Jones case for Texas Monthly in 1983, and in his 1989 book, “The Death Shift: Nurse Genene Jones and the Texas Baby Murders.”